Evidence-based Cycling Education

Our goal was to make research from the Cycling in Cities program, and elsewhere, into tools that are useful for policy-makers, planners, and the public. We received funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research for a project with two components: an evidence-based audit of education materials related to cycling; and a bikeability tool called Bike Score.

METHODS

This project had three steps:

- review of the scientific literature on cycling safety;

- review of cycling-related educational materials used across Canada;

- comparison of the scientific evidence to the safety-related messaging in the training materials.

FINDINGS

We identified 56 scientific articles focused on crash or injury risk, injury severity, or other safety outcomes that met our inclusion criteria. The evidence covered bicycle-motor vehicle interactions, route characteristics & conditions, route types, bicycling operations, and safety equipment. Two meta-analyses of helmet research were also reviewed.

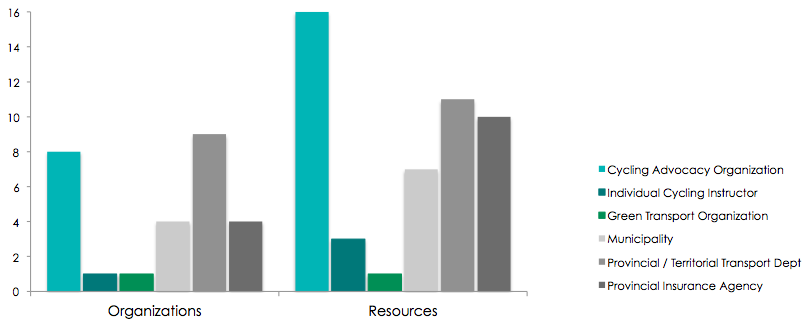

We gathered 48 education materials for cyclists and/or drivers from provincial and territorial driver’s licensing jurisdictions, municipalities, and non-governmental organizations. Materials covered bicycle-motor vehicle interactions, route characteristics & conditions, route types, bicycling operations, safety equipment, bicycle fit and maintenance, and rules of the road.

Sources of cycling-related education materials for this project

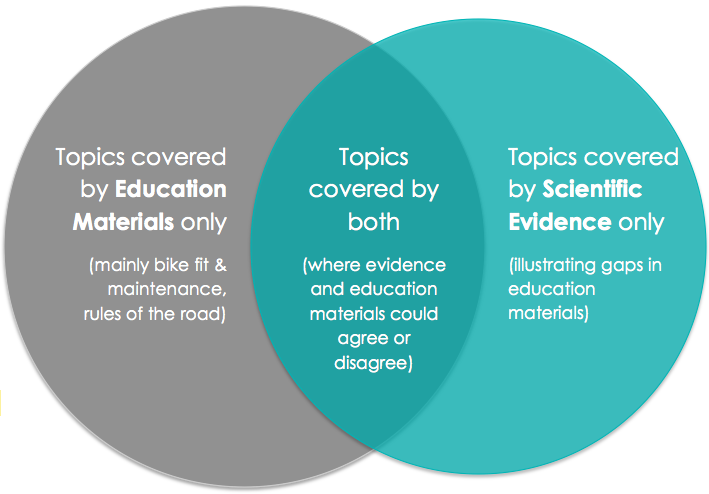

Overall, we found that many of the principles covered in cycling education materials were supported by scientific evidence. A gap in the educational materials was information to help cyclists plan their routes, including scientific evidence about the relative safety of different route types, and route characteristics and conditions. In addition, evidence on motor vehicle passing distances was not included with education messages about where to cycle on the road.

Many education messages were not addressed in the scientific literature at all, but still provided useful information about potential hazards (e.g., gravel, cars pulling out of driveways), bicycle fit and maintenance (e.g., brake condition), and rules of the road (e.g., hand signals). Some important information on cycling-related traffic rules was rarely explained, e.g., how to behave where there are bike boxes, sharrows or traffic circles. A problem in some education materials was uncited, ambiguous “facts” that may be misinterpreted as suggesting causes of crashes or injuries.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the results, we proposed the following to improve cycling training materials:

- Review your organization’s education materials compared to the scientific evidence presented in this report to ensure that all elements your organization wishes to convey are included.

- Include information about the relative safety of route types and route characteristics to help cyclists plan their routes, in particular:

- decreased risk associated with bike-specific route types, including cycle tracks, bike lanes, and bike paths,

- decreased risk associated with routes with low traffic volumes, including residential street bike routes,

- increased risk associated with roundabouts or traffic circles at intersections, and

- increased risk after dark on routes without streetlights.

- Include information about motor vehicle passing distances, so cyclists understand circumstances when motor vehicles are likely to pass closer to them, in particular:

- where motor vehicle speeds and traffic are high,

- where there is motor vehicle traffic in the opposing direction, and

- when the passing vehicle is a heavy vehicle such as a truck or bus.

- Include information for cyclists and drivers about the rules of the road for bike-related infrastructure, such as bike lanes, traffic circles, bike boxes, and sharrows.

- Remove or carefully explain data that does not provide the basis for drawing conclusions about relative safety.

- Cite sources of information used so they can be checked and updated.

- Update training materials from time to time with new scientific evidence about factors affecting cycling safety.

KNOWLEDGE PRODUCTS

- Evidence from Safety Research to Update Cycling Training Materials in Canada [Report]

- Safety Evidence for Bicycling [summary]

- “Is evidence in practice? Assessing how cycling education materials reflect research evidence”, Victoria, August 2014 [presentation]

- Transportation Research Board, Washington DC (won Committee on Bicycle Transportation Outstanding Paper Award), January 2013 [Poster and Paper]

- “Using evidence from injury studies to update cycling training materials in Canada” VeloCity, June 2012 [presentation]

- Winters M, Weddell A, Teschke K. (2013). Is scientific evidence in practice? A review of driver and cyclist education materials with respect to cycling safety evidence. Transportation Research Record, 2387:35-45. [article]

FUNDING

Funding for this project was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.